Ads not shown when logged in

-

Automated Tracker

Refreshing Beer - Whatever happened to Pils?

Refreshing Beer - Whatever happened to Pils?

Visit The Refreshing Beer site

Strange question, I know. Isn’t Pils, or a bastardised descendant of it, the most popular beer style in the world?

Perhaps. But the term was understood much more narrowly in 1980s Britain by most beer drinkers. It wasn’t a hoppy golden lager modelled on the intensely bitter beer pioneered by Josef Groll at Pilsner Urquell. Nor was it the rather lighter version of it popularised by Dutch and Belgian brewers.

It was this stuff:

There were competing products, but if you asked for Pils in the 1980s you would generally be given a bottle of Holsten Diät Pils. For a generation, drinkers believed that a Pils was a strong bottled lager with gothic type on the label.

How to understand this bizarre phenomenon? Put on a Krautrock LP and accompany me to 1970s Germany, as we ask: What is a Diät Pils anyway?

In the 1960s and 70s it was quite common for German brewers to form a sort of consortium to brew a particular beer. These were typically products which you considered you had to have in your range, but did not sell in great quantities: things like alcohol-free beer, Malzbier (a very sweet non-alcoholic product thought suitable for children), or the not yet fashionable wheat beer.

Brewers benefited from being able to offer these products, without having to promote beers from a direct competitor.

From around the early 70s onwards, one of these niche products was a particularly highly attenuated beer, which as a result was very low in carbohydrates and thus seen – in the nutritional understanding of the time – as suitable for diabetics. In some other countries, diabetics might have just been told to avoid beer, but that was clearly not thought of as an option in beer-drinking Germany.

In West Germany, these low-carb beers were marketed as “Diät Pils” or just “D-Pils”. Imitators in the East went the whole hog and labelled themselves Diabetiker-Pils.

The members of the D-Pils consortium – Holsten of Hamburg; Wicküler, Wuppertal; Spaten, Munich; – at least initially shared common branding for the product. Diät-Pils was the brand, with the actual brewery in second place.

|

| D Pils was the brand much more than the particular brewery. Here we have an almost identical label used by Henninger of Frankfurt (above) and (below) Wicküler of Wuppertal. |

Although some drinkers who weren't diabetic enjoyed the particularly dry finish of these beers, it remained a niche. But according to legend, German Diät-Pils beer was also the inspiration for the (in its own terms) groundbreaking Miller Lite, when John Murphy, the president of Miller, encountered it on a business trip.

How did this marginal speciality beer come to be one of the biggest brands in the British beer market in the 1980s?

Holsten Pilsner had been sold in Britain since the 1950s. But it was not the same beer that later became a top seller.

|

| This advert from a 1958 programme for the pantomime “Cinderella” (starring Tommy Steele, and Kenneth Williams, who was not yet a big star, mainly known for doing the funny voices on Hancock’s Half Hour) invites the thirsty panto-goer to enjoy a “high-gravity and full-flavoured” Holsten in the interval. |

In the late 1950s and early 1960s the Holsten Pils being imported was between 4.5% and 4.9%, probably very similar or identical to the product on sale back home in Hamburg-Altona.

Once Diät-Pils was developed in Germany, at some point in the 1970s a decision was clearly made to import the Diät Pils instead and to promote it heavily in the UK market.

|

| We can see the initial branding used by Holsten in the UK is basically identical to the generic D Pils brand |

In the 1980s so-called “premium lager” was the next big thing, as drinkers realised the watery draught lager nonsense they‘d been drinking wasn’t the real deal, and traded up to more fashionable bottled products.

“More of the sugar turns to alcohol,” ran the tagline, alluding to strength in a way that got round the rules. The reference to the specially high attenuation was taken by drinkers to mean not so much “you can drink this if you’re diabetic”, but more “this will get you pisseder, faster”.

In comparison to most British beers, Diät Pils was a alcoholic monster: 45% stronger than a 4% bitter and nearly twice as strong as mild or the draught ersatz “lager” people had been drinking before.

Why this was necessary remains a mystery though, as even the 4.8% of regular Pils would have been regarded as very strong by the British standards of the time.

Holsten Diät-Pils was a pioneer in its day: Michael Jackson wrote: “Its real virtue is that it is a genuine import, with plenty of hop character.” You could argue that Holsten basically created the premium lager market; this was before the likes of Stella Artois achieved any national prominence (even though Whitbread had been pushing it since the early 1970s). By the late 80s, Holsten not only dominated the bottled pils category with 65% market share, but was 33% of all premium packaged lager in the on-trade – a dominance that is almost unimaginable today.

The high point of its popularity must have been the mid- to late 1980s, when Holsten was spending £6million a year on advertising, with TV adverts featuring the latest CGI technology which was used to insert Griff Rhys Jones into classic black and white movies.

Two interesting features of these 1984 ads are the contemporary label in the bottle shot, still bearing the large stylised D from the Diät-Pils consortium, and the word Pils in huge blackletter type. The name of the brewery, on the other hand is hardly recognisable in the early ads, but during the run of these commercials someone hit on the idea of having the name of the brand large enough to be legible.

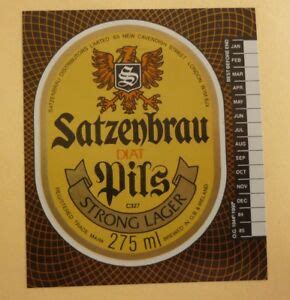

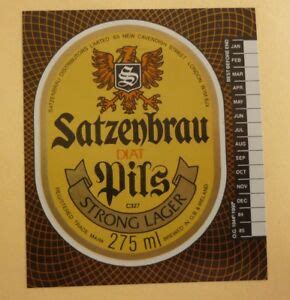

Like any pioneer, Diät Pils attracted copycats: Satzenbrau, LCL Pils from the club-owned Federation Brewery, Kaltenberg from Whitbread (which was also, at least initially, a genuine import), Edelbrau from JW Lees. For a time, every pub needed a Pils.

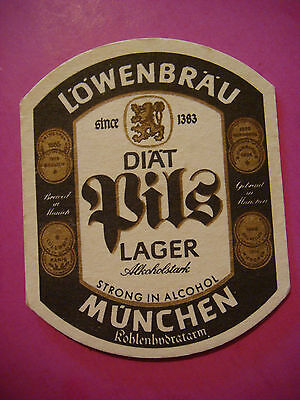

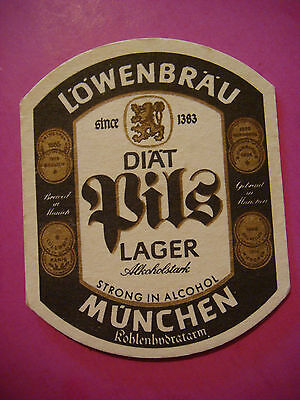

And so for a generation of British drinkers, Pils did not necessarily mean a hoppy beer: it meant strong lager in a half pint bottle with a yellow label with Gothic script on it. Only Allied’s Löwenbräu Diät Pils (initially imported and then brewed in Wrexham) bucked the yellow trend with its attractive white, black and gold colour scheme.

As inevitably happens, Diät Pils eventually had to go out of fashion – superceded by trendier, newer beers that became established brands (Stella) or are now nearly forgotten (Red Stripe, Beck’s, Grolsch).

The regular Holsten Pils in Germany seems to have remained quite stable in gravity for sixty years, although it is probably less bitter than it used to be. It was 4.8% in 1961 and is the same ABV today.

That cannot be said for the British version, which is now 5.0% and made with glucose as well as malt. It was cut to 5.5% in 1993, and has fallen further since. The Holsten Pils sold in the UK now has little in common with the beer that made its reputation, except the yellow label and the oddly angular lettering in the word Pils, a vestigial reminder of the blackletter it used to be.

In Germany itself, thinking on the nature of diabetes has changed and it is no longer permitted to market beers specifically as suitable for diabetics. Some of the beers themselves still exist, and have been renamed. But none of them shape the beer market in the way that Holsten Pils once did in the UK.

More...

Similar Threads

-

By Blog Tracker in forum Blog Tracker

Replies: 0

Last Post: 27-02-2018, 14:15

-

By Blog Tracker in forum Blog Tracker

Replies: 0

Last Post: 03-02-2016, 15:14

-

By Blog Tracker in forum Blog Tracker

Replies: 0

Last Post: 14-08-2014, 08:45

-

By Blog Tracker in forum Blog Tracker

Replies: 0

Last Post: 06-10-2012, 09:13

-

By Blog Tracker in forum Blog Tracker

Replies: 0

Last Post: 14-07-2011, 17:57

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote